So many things were not taken into consideration as they might have been. The master monk is drawn to be a religious fanatic, a despot, a dictator, and a truly brutal man, accompanied by too compelling other brothers, an elder, and a younger. But it just didn’t work - not for this reader, in any case, and I have to say that I feel the author has left us with one of the ugliest central characters at the heart of what could have been a far more generous and indeed glorious novel. Donoghue for being able to call from her literary and conversational research some really wonderful disclosures about how sixth-century men might have made their way there, and labored to create a monastic settlement in the sea. I must say, I find this a disqualification for the labor she undertook in trying to imagine and describe the first monastic settlers to this place of resurrection - a weird trinity of wonderfully different characters. I find myself days after the completion of its reading, still arguing and wrestling with Donoghue, the author, who only at the end of the story confessed that she had never been there. And though there were moments of marvelous description and intuition about how the founding trio of monks may have found their way to survive briefly this most rugged and unforgiving rock mountain in the sea, none of these moments added up to what the promise of the book was.

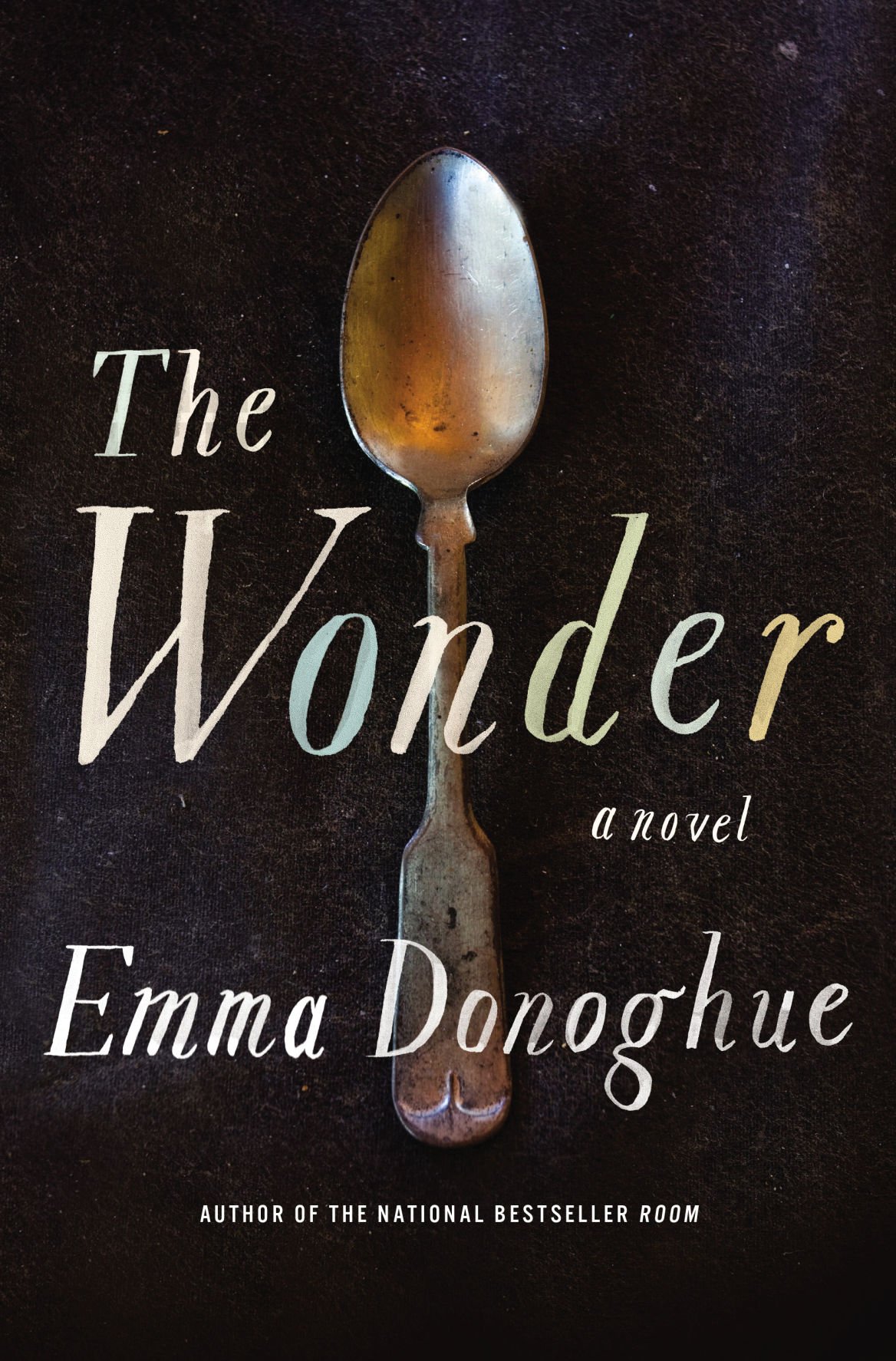

Three Men in a Boat it is not, Artt being ‘zealous for all hardships’.As one who has scaled the arduous ascent of Skellig Micheal on several occasions, I was so eager to read this book with its promise of insight and imagination. He picks two monks – one old, Cormac, a storyteller, and one young, Trian, a musician – and off they sail. Set in the 7th century, a holy man called Artt has a dream vision directing him to ‘withdraw from the world, set out on a pilgrimage with two companions’, find an island and found a monastic retreat. This must surely be her most Catholic novel. I thought this when reading her 2020 novel The Pull of the Stars, set in the 1918 flu epidemic, and Haven is no exception. Also, it has to be said that she’s frightfully good at suffering and endurance. The Irish-Canadian novelist Emma Donoghue doesn’t entirely qualify as a Catholic writer, even though she’s on record as saying she’s currently obsessed with Catholic theology, specifically Purgatory, but there’s a thread of Catholicism (particularly the Irish variety) in many of her books. I used to envy Catholic novelists – Graham Greene, Muriel Spark, François Mauriac – as having that extra point of view, namely eternity.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)